What happened to the startups of yesteryear?

Category: Uncategorized

Here at Beauhurst, we track equity investment in UK companies. We know that a lot of young businesses use equity finance to fuel their growth, so we treat it as a key indicator of their potential. We’ve selected a cohort of startup companies that raised equity finance in 2011. 893, to be exact. By tracking this select cohort, we’ve had a chance to examine their progress in detail.

Success stories

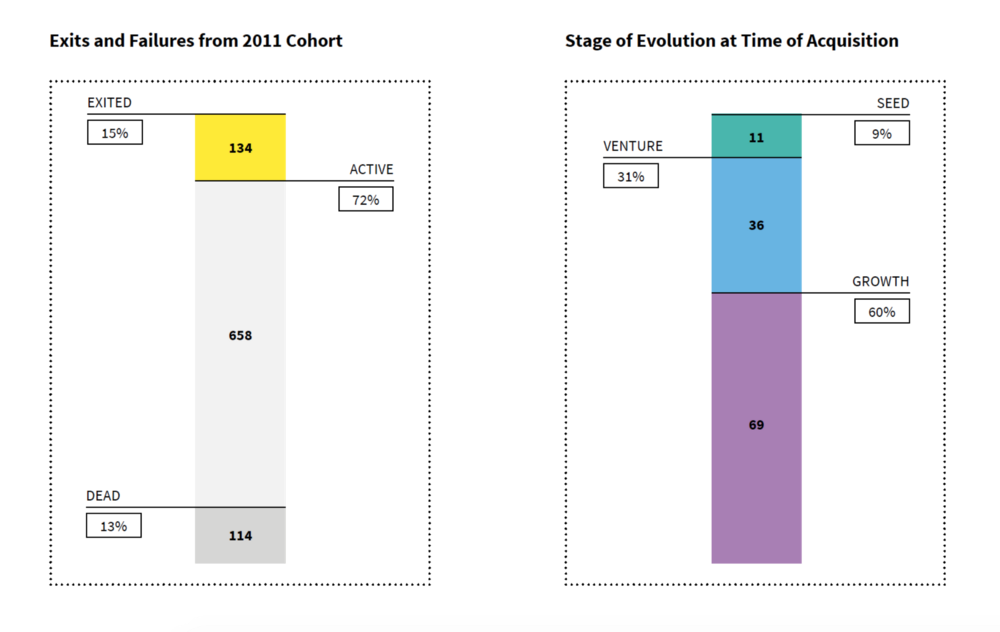

15% of the businesses we examined have exited, meaning they’ve either been listed on a stock exchange or sold.

IPOs

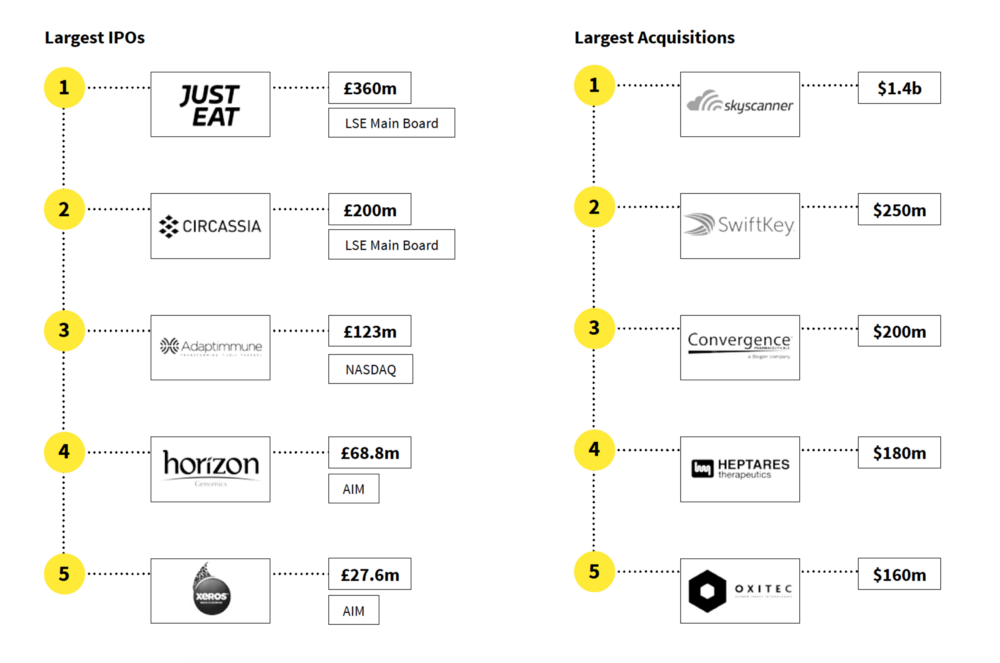

Of the 2011 cohort, 18 companies (2%) floated on public stock exchanges, predominantly AIM. The two largest IPOs, however, were on to the LSE main board. Between them, these 18 companies raised a total of £940m across their initial public offerings.

It will come as no surprise that all but two of the companies were strongly technology-based. More strikingly, however, a third of the companies that listed were operating in the life sciences space. As drug development processes are extremely capital intensive, it makes sense that these businesses would turn to public markets, rather than individuals or venture capital funds, for the backing they need.

Acquisitions

13% of the businesses that raised equity money in 2011 have since been acquired: some were acquired by private equity funds, and some were acquired by other companies. The most common types of acquirer were companies based in the UK, with US firms not far behind.

The majority of businesses were acquired at a later stage of their development (typically with significant revenue and likely some profit), which makes sense: by that point they were large enough for their acquirer to notice them. The largest acquisition was that of Skyscanner, acquired by Ctrip for £1.4bn.

It is reassuring to see so many acquisitions, and at such high valuations. But the real question is whether there are more of these to come — and if so, how many?

On average the 116 businesses in the 2011 cohort that were acquired raised £12.3m of funding before being acquired; whereas the average amount raised by the whole cohort is £8.5m. Similarly, the acquired companies had been incorporated for ten and half years before being bought, whereas the average age of each company in the cohort is just over 9 and half years.

Best of the rest

There are still 658 companies that have yet to exit (and therefore continue to be tracked by Beauhurst), and based on the above they’ll need to raise a little more money and trade for a little longer before they can expect to exit in this way.

On average, where we’ve been able to calculate a valuation, the pre-exit companies were worth £2.97m in 2011. They’re now worth £12.7m, an increase of 328%.

Whilst valuation growth doesn’t substantively prove that the underlying businesses are doing better, it shows that investors are confident enough in their prospects to pay more for a stake in them.

The Failures

Above we’ve focused on the successes, the growths, the exits. But what’s

the story when we look at ventures that didn’t go quite as planned?

Below we look at the companies that have died: this is when a company has gone into liquidation and eventually ceased trading. As we often hear, 90% of all startups fail, but what does receiving investment do to these odds? Are there certain sectors that are more vulnerable to failure, even once they have received equity backing?

In the same cohort of companies that raised equity in 2011, 12% are currently classified as dead. But this figure isn’t uniform across sectors,

and it is this disparity that proves interesting when we delve a little deeper.

Case study: Aquamarine Power

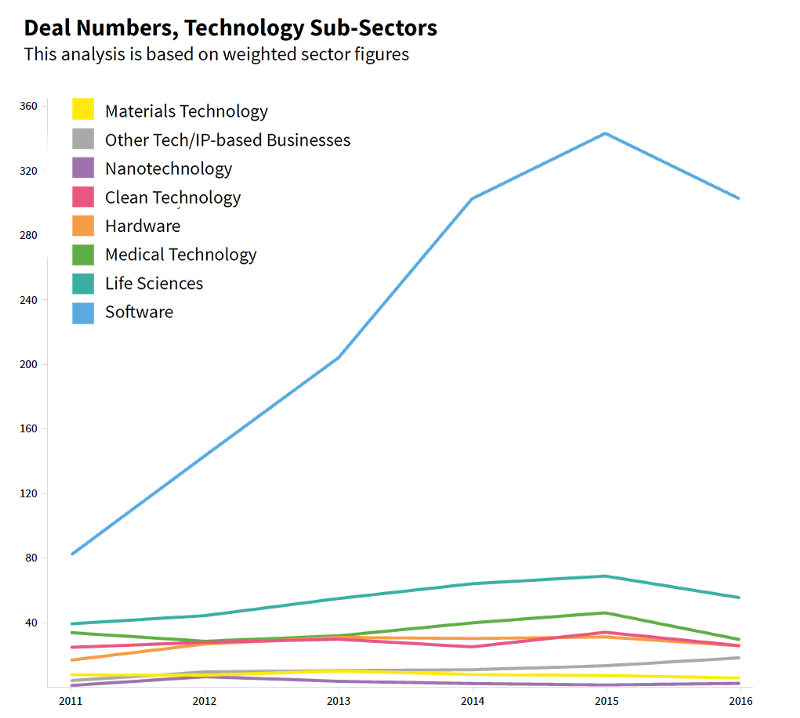

“CleanTech” is a sector that receives a lot of buzz off the back of its green credentials. In 2011 we witnessed 93 equity investments totaling £221.5m into 87 such companies. Of these companies, 21% are now dead.

This is significantly greater than the cross-sector average, which raises questions as to the reasons behind this apparent high failure rate. Is it the relative youth of this sector? The macro climate of falling fuel prices?

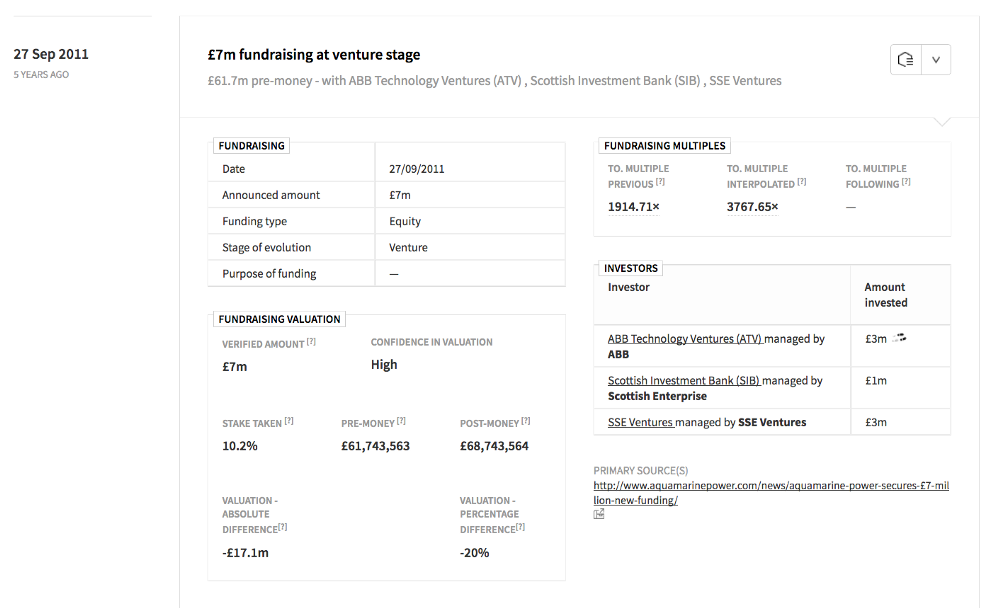

One of these dead CleanTech companies is Aquamarine Power. The company received more investment than any other companies in that sector from the 2011 cohort: £53.7m between 2009 and 2014. It was based in Edinburgh, developing and manufacturing technology that uses waves to produce electricity.

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding its progress and the numerous grants received from the EU and Innovate UK, its valuation peaked at £85.9m, following a £17.7m investment in January 2011, and successively fell until the firm ceased trading in November 2015. Aquamarine Power cited the economic climate and the lack of private-sector backing as the reason behind its rapid demise.

With government plans to create Europe’s largest CleanTech hub in London in partnership with the Imperial College Centre for CleanTech Innovation, and with the support of the London Sustainable Development Commission, the chances for similar ventures might be set to improve.

Other sectors

At the other end of the spectrum sit the banking and financial services companies of the 2011 cohort. The 45 companies received funding totaling £138m in 2011. Strikingly, only 2% of these companies are now classified as dead. So it should be no surprise that London has been named the world’s leading city for Fintech in a recent report commissioned by the Treasury.

Another sector with a similarly low company death rate is Life Sciences, where only 7% of the companies that raised funds in 2011 are now dead. The UK government’s industrial strategy indicates increased support for Life Sciences; but government support is already having an impact in the sector, as it is across the whole cohort.

Innovate UK grant recipients in the 2011 cohort had a failure rate nearly half the average, at 4%.

So what have we learned?

The findings from this cohort are positive. The chances of a successful exit are high across all sectors, and the most likely kind of exit is an acquisition by another UK company. The chances of an equity-backed businesses failing (after five years) are lower than the chance of exiting.

Some sectors are more prone to failure than others, while companies that have received public grants are less likely to fail. Even if companies haven’t been acquired or floated (or gone bust), on average their paper value has increased.

This is how things stand after five years with this cohort of businesses. It indicates a positive outlook for high-growth companies in the UK. However, could it be that the current climate is less conducive to success?

We will have to wait and see.

Discover the UK's most innovative companies.

Get access to unrivalled data on all the businesses you need to know about, so you can approach the right leads, at the right time.

Book a 40 minute demo to see all the key features of the Beauhurst platform, plus the depth and breadth of data available.

An associate will work with you to build a sophisticated search, returning a dynamic list of organisations matching your ideal client.